29/10/18

The brief:

To keep a diary for at least 2 weeks and then interpret it into a photographic project, using your own experience to explore your identity in some way, either directly or indirectly.

I have attempted to keep a diary many times over the years and have never been very successful in keeping it up for any length of time. I lose track, forget to do it for a few days and then struggle to restart. I have tried keeping short notes, writing long screeds, taking a photo a day and posting it online in the various social media sites, writing (bad) poetry. All with no real degree of success. Two weeks seemed manageable, and it was – just. I used a combination of notes on what had actually happened that day, thoughts that they gave rise to and an image, either taken on the day or sometime recently to make a page a day diary. In the end I actually quite enjoyed it.

Thoughts:

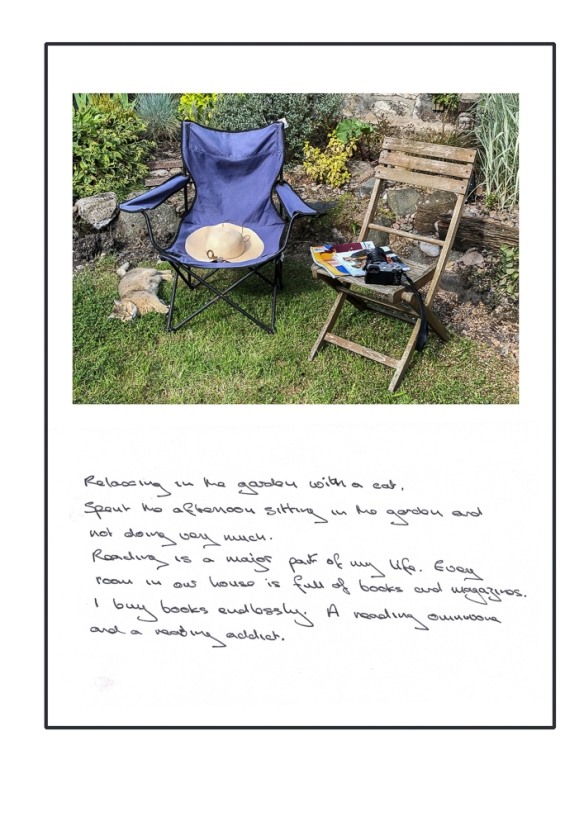

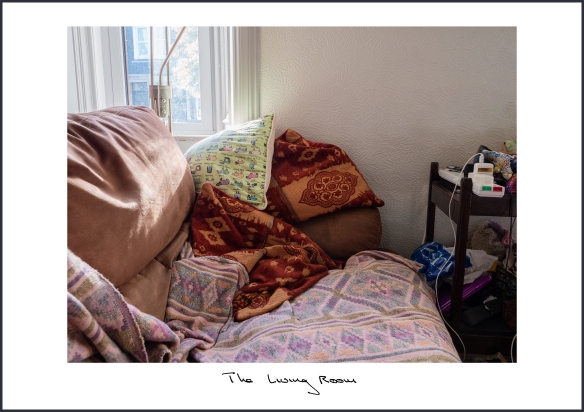

When I went back over it I realised that most of what I do is very repetitive and banal. Yes, I went shopping. Yes, I went to work. Yes, I read and pottered in the garden. Most of my days were spent circling around the same activities in the same place, living room, study, garden, kitchen, office. The place defined what I did. I sit and read in the living room. I do my photo work in my study. I sit and relax in the garden. I sit and eat in the kitchen. I sit and do paperwork in the office at work. The common theme is sitting. No one else sits in my places, or only very rarely. I am sitting at my study desk to write this. I just took a break sitting on the couch in the living room. I don’t need to be in the picture to describe what I am doing. The place tells me the activity and brings back memories. The chairs describe my life.

Research:

It has been said that all art is autobiographical in nature. Certainly, all art and literature says as least as much about the author as about the subject. Fellini said ‘“All art is autobiographical; the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography” and “Even if I set out to make a film about a fillet of sole, it would be about me” when talking about his films (Fellini, 1965). Autobiographical photography can be produced in a variety of ways and does not always need to involve direct self-portraiture. The work of Nigel Shrafran is a good example of this as is that of Sophie Calle in Take Care of Yourself. (Calle, 2007)

https://scottishzoecontextandnarrative.wordpress.com/2018/10/20/self-absented-portraiture/

https://scottishzoecontextandnarrative.wordpress.com/tag/sophie-calle/

While thinking about indirect self-portraiture I read this article about photographing items recovered from a devastating forest fire, which also uses small items to describe a life, in this case, a part of a life history that has now been destroyed. They are very personal and poignant. The remnants of jewellery, parts of a burnt doll, the blades from a food mixer. They clearly tell a story of a home and family and the things that made up that home, now gone. (Smithson,2018)

http://lenscratch.com/2018/10/norma-i-quintana-forage-from-fire/

Another photographer whose work is often considered to be mainly autobiographical is Masahisa Fukase. His work is wide-ranging, and on the surface about Japan and the people and culture there, however he himself relates it to taking images that talk about himself. For one series of images about his cat Sasuke he says “I didn’t want to capture the most beautiful cats in the world, but rather their charm with my lens while being reflected in their pupils. One might accurately say that this collection is really a ‘self-portrait’ for which I adopted the form of Sakuke and Momoe” and also “I photographed ravens for ten years, at the end of which I realised that the raven was indeed me” (Fukase, Kosuga &Baker, 2018). The positive and negative sides of his personality, dark and light, play and despair.

Practice:

I took a series of pictures of the 5 areas at home and work where I spend most time. I did not tidy them up in advance. I did try some images where I had ‘organised the scene’ but these did not show the daily life that really happens, and I am not a naturally tidy person.

I picked a series of 5 images that I felt were most representative of my life. Certainly my family would be able to immediately identify what I would have been doing at any of these points.

I considered various ways of showing them:

- Monochrome versus colour

- Stand alone images versus shown with titles – handwritten or typed

- Paired with handwritten sections taken out of my two weeks of diary entries.

Final Choice:

I decided that simple was the best option, and to use a colour image with a handwritten title.

References

Calle, S. (2007). Sophie Calle – Take care of yourself. Arles: Actes Sud.

Fellini, F. (1965). The Atlantic.

Fukase, M., Kosuga, T. and Baker, S. (2018). Masahisa Fukase. Paris: Editions Xavier Barral, p.148.

Smithson, A. (2018). Norma I. Quintana: Forage From Fire. [online] LENSCRATCH. Available at: http://lenscratch.com/2018/10/norma-i-quintana-forage-from-fire/ [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

Appendices:

added as a PDF so available as a download

Contact sheets: