26/02/18

Susan Sontag published ‘On Photography’ in 1977. It is a collection of essays about photography and its role in the world at that time. The mid to late 70 ‘s was a time of general public cynicism. Woodstock was past, and the flower power children had grown up. Watergate had happened, Britain had voted Labour out and Conservatives in.

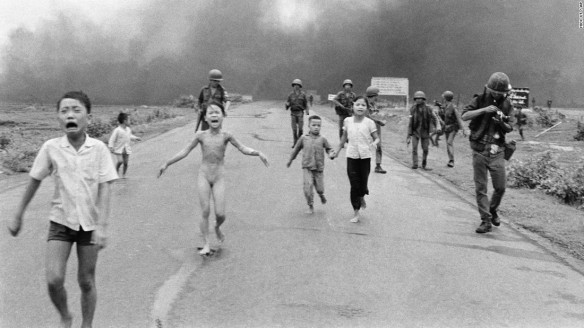

America had just come out of Vietnam in 1973 and the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese was in 1975. There had been massive fatalities on both sides. One of the most famous of war journalism images is the Nick Ut photo from 1972 of a young girl fleeing after a napalm attack. The still image shocks, can be looked at over and over – but how many people know the story behind it now? Ut took the child to an American resource, and she was then treated in Germany. She went on to attend university, got married and had children, eventually setting up a foundation to support medical and psychological child victims of war. The image became a landmark one of the atrocities of war and was partially responsible for the public outcry against American involvement.

© Nick Ut

By 1977 the USA and most of the world was in the midst of a massive phase of inflation and concomitant job shortages. Music had stopped being ‘happy’. The most bought album of the period was ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ by Pink Floyd, with its tracks about ‘Money’ and ‘Time’:

Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day

You fritter and waste the hours in an offhand way.

Kicking around on a piece of ground in your home town

Waiting for someone or something to show you the way.

Tired of lying in the sunshine staying home to watch the rain.

You are young and life is long and there is time to kill today.

And then one day you find ten years have got behind you.

No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun.

So you run and you run to catch up with the sun but it’s sinking

Racing around to come up behind you again.

The sun is the same in a relative way but you’re older,

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death.

Every year is getting shorter never seem to find the time.

Plans that either come to naught or half a page of scribbled lines

Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way

The time is gone, the song is over,

Thought I’d something more to say.

Susan Sontag says,’ War and photography now seem inseparable, and plane crashes and other horrific accidents always attract people with cameras. A society which makes it normative to aspire never to experience privation, failure, misery, pain, dread disease, and in which death itself is regarded not as natural and inevitable but as a cruel, unmerited disaster, creates a tremendous curiosity about these events—a curiosity that is partly satisfied through picture-taking. The feeling of being exempt from calamity stimulates interest in looking at painful pictures, and looking at them suggests and strengthens the feeling that one is exempt’ and ‘Protected middle-class inhabitants of the more affluent corners of the world—those regions where most photographs are taken and consumed—learn about the world’s horrors mainly through the camera: photographs can and do distress. But the aestheticizing tendency of photography is such that the medium which conveys distress ends by neutralizing it. Cameras miniaturize experience, transform history into spectacle. As much as they create sympathy, photographs cut sympathy, distance the emotions. Photography’s realism creates a confusion about the real which is (in the long run) analgesic morally as well as (both in the long and in the short run) sensorially stimulating’. She goes on to talk about her feeling that even ‘the most compassionate photojournalism’ runs a fine line between raising our concern about a particular event and distancing us from the event because they are superb images in their own right. What is read from an image is heavily dependent on any accompanying text, and also the context in which it is shown. The photograph itself ‘is mute’. Sontag also argues that the photographers who take the images, of war, of social distress and societal disaster are not directly involved. The are (often middle-class) onlookers, albeit with a ‘good conscience’ and a desire to improve the lives of others. However, ‘By getting us used to what, formerly, we could not bear to see or hear, because it was too shocking, painful, or embarrassing, art changes morals ….. our ability to stomach this rising grotesqueness in images (moving and still) and in print has a stiff price. In the long run, it works out not as a liberation of but as a subtraction from the self: a pseudo-familiarity with the horrible reinforces alienation, making one less able to react in real life’ (Sontag, 1977).

So – compassion fatigue, the idea that the more you look at images of disaster the less affected you are, the more you see the less you care. This thought is echoed in the Rosler essay ‘In, Around and Afterthoughts’ from 1981 where Rosler comments that documentary images are now mainstream and the response to them can be ‘send money’ (Rosler, 1981). Sontag argues that for images to be ‘shocking’, and therefore, presumably effective, they have to be more and more disturbing to break though the barriers of familiarity and ennui.

Is this accurate? A recent article in the British Journal of Photography about the work of Anastasia Taylor-Lind takes a very different viewpoint. She was involved in the Human Rights Watch coverage of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. She, among other images, took a series of portraits of people who had survived the massacre. ‘While war doesn’t look like the gentle, tender portraits I made, I wonder whether it’s a failing of photojournalism that we tend to represent victims of war at their most disparate and vulnerable’ (Butet-Roch, 2018). Do we take away what is left of the victim’s dignity? A similar path has been taken by Laura Guoke who painted portraits of people in the Ritsona refugee camp in Greece. ‘I am more and more convinced that the works created by artists should encourage people to understand, to sympathise, to admire and to wonders what could be done by each of us’ (Guoke, 2017). These two images, using different media, and from different places are startlingly similar.

- © Anastasia Taylor-Lind

- © Laura Guoake

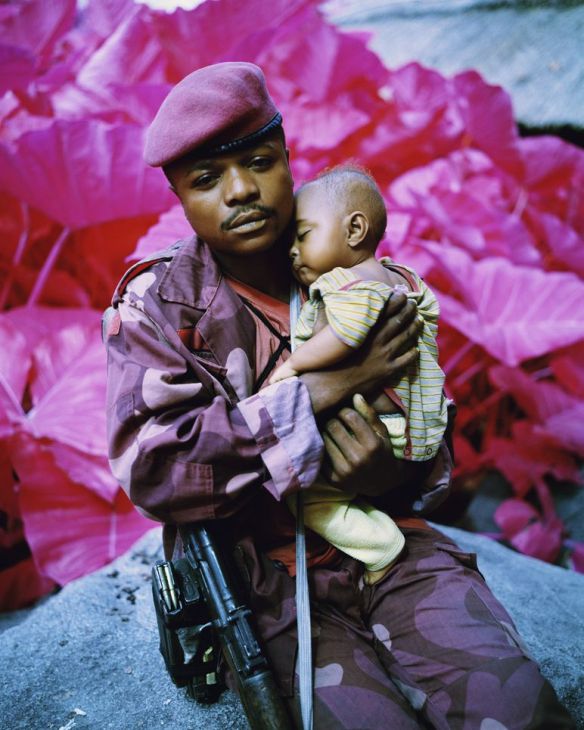

An alternative view is shown by Richard Moses in his video installation ‘Incoming’ where he uses heat sensitive cameras to show refugee camps and in ‘Infra‘ with hot pink images of soldiers shot with an infra-red film in the Eastern Congo. The camera is a weapon here – referencing Sontag comment ‘the Camera is a sublimation of the gun’. His camera is literally classified as weapons technology. Most of his images show disaster and destruction, children at war, massive camps of faceless refugees – but I keep coming back to the one of a soldier and a child.

© Richard Mosse – Madonna and Child

All these images, admittedly picked by me, contain children. Are we, as a race, more likely to be compassionate when children are the subject? I find images of vulnerability and pride more moving than those of terror and destruction. Is this because we now live in a different era? Are we exhausted by the scenes of distraught people fleeing terror? Does there need to be a balance, to show both sides of the story? Is it simply because of my personal take – I am more interested in healing than destruction, or because I, like Taylor-Lind and Guoke, am female?

Has my view changed after thinking about ‘aftermath’ photography? Probably not. For futher thoughts on this see:

References

Butet-Roch, L. (2018). Anastasia Taylor-Lind shows Rohingya women’s dignity amid horror. [online] British Journal of Photography. Available at: http://www.bjp-online.com/2018/01/anastasia-taylor-lind-gives-rohingya-women-dignity-amid-horror/ [Accessed 25 Feb. 2018].

Guoke, L. (2017). BP Travel Award 2016: Laura Guoke – National Portrait Gallery. [online] Npg.org.uk. Available at: https://www.npg.org.uk/blog/bp-travel-award-2016 [Accessed 25 Feb. 2018].

Pink Floyd (1973). Dark Side of the Moon – Time. London: Harvest Records.

Rosler, M. (1981). Martha Rosler. Halifax, N.S.: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Richardmosse.com. (2018). Richard Mosse | Infra. [online] Available at: http://www.richardmosse.com/projects/infra [Accessed 25 Feb. 2018].

Sontag, S. (1977). On Photography.