25/05/18

Sophie Calle – Take Care of Yourself

© Sophie Calle

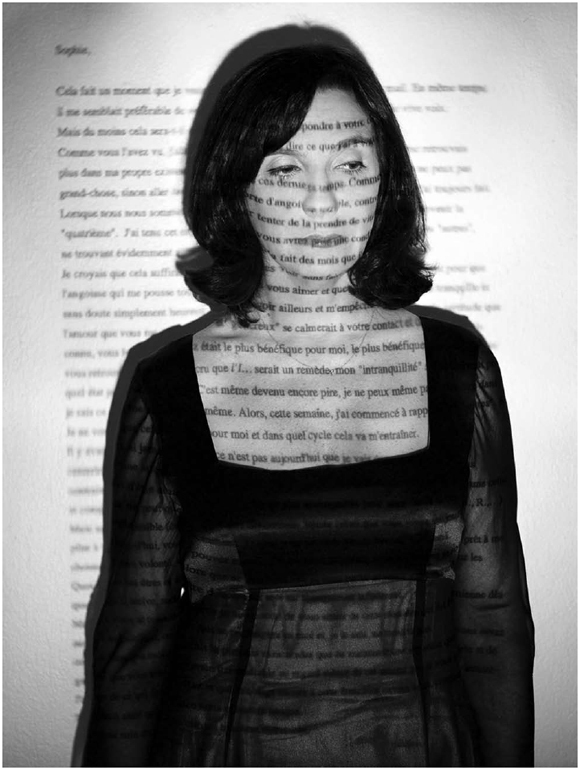

Reading the email sent to Sophie Calle in an English translation (Slow Words, 2016) I thought I would write my own response, as a doctor who deals with many people with mental health problems.

The writer is self absorbed, narcissistic in the extreme. He claims that he has a severe anxiety and blames Calle for his problems. He uses her ‘rules’ as an excuse for ending the affair. He writes so as to make her feel guilty ‘I am prepared to bend to your will’ and then does exactly the opposite to what I assume she would have wanted. The email is potentially very damaging to the person it is sent to ‘remember I will always love you in the same way, in my own way,’ implies a possibility that the relationship is only on the back burner, that it could reignite. I would think it is likely that the writer has a borderline personality disorder, and that all his relationships are likely to be fraught with disaster and only on his own terms. He is at risk of threatening suicide, or even suicidal attempts to gain attention. Treatment is difficult, medication ineffective, specialist treatment with dialectical behaviour therapy or mentalisation-based therapy can be useful as can living in a therapeutic community (nhs.uk, 2016). People with BPD are difficult to have a sustained relationship and usually blame this by implication on the other people in their lives.

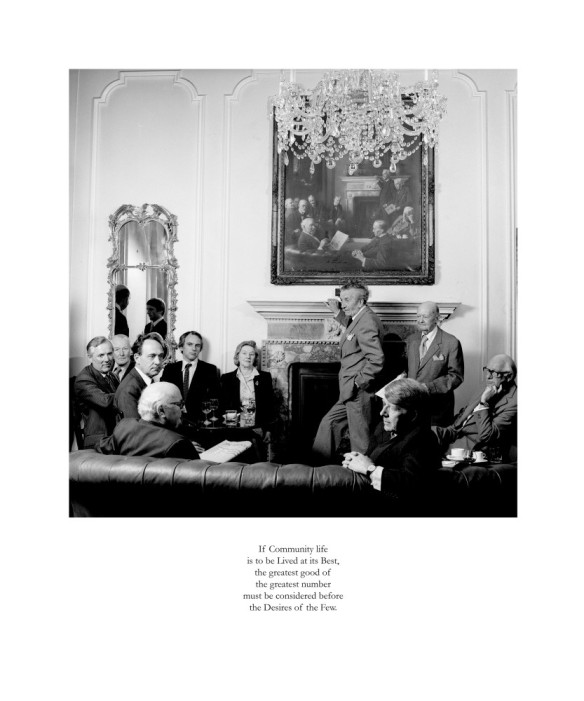

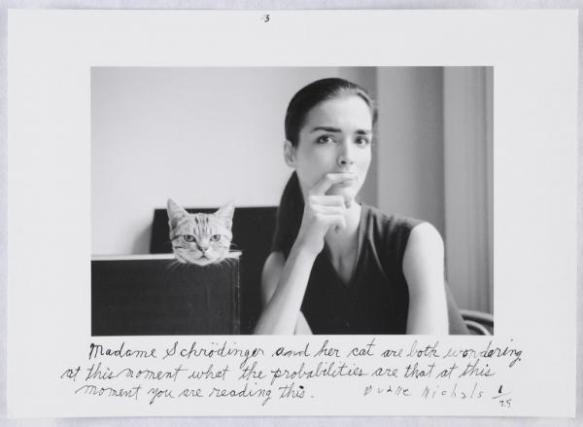

Calle deals with the email by sharing it with others, eventually turning it into apiece of conceptual work where she asks 107 professional women to analyse it in the format that best suits them, ranging from scientific assessment of the language, though poetry and a crossword to dance and photographs them while they are doing so. This enables her to avoid reading and re-reading the email. She says “After a month I felt better. There was no suffering. It worked. The project had replaced the man” (Chrisafis, 2007).

An article in the Guardian places ‘Take Care of Yourself’ in the context of Calle oeuvre, talking about how she uses her own emotional life to find subjects, such as the death of her mother, a film about marriage and a project on spotting mistakes in journalists’ articles. It says, ‘Calle will continue to deal with what annoys and hurts her by turning it into a game’ (Chrisafis, 2007). Cora Fisher in the Brooklyn Rail feels that if ‘X’ had anticipated the response he would not have written the email. Calle has used it to produce a series of ‘privileged interpretations, translations of reality……. Dead seriousness to comic relief’ (Fisher, 2009). She clearly feels that that Calle has used this both as a therapeutic opportunity and as a demonstration of feminine, and possibly feminist thought. Clare Harris writing in a.n saw the exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and was disappointed in the presentation as she found it left her feeling ‘engulfed and frustrated’. However, she notes that Calle is ‘fostering debate on the social rules that govern sex and love’ and ‘As we can all relate to being rejected at some point in our lives, we are drawn to this work, and distanced from the pain’ (Harris, 2010).

All these reviewers were positive about Calle’s work, and about this particular piece, which I think has to be considered as one piece of work, complete in itself, not as a series of individual images and writings. Interestingly, all the reviews I found were by females and I wonder what the male take on this would be, whether it would be so positive or whether the feminist slant and the sometimes negative comments on the male protagonist would have changed their responses.

Sophy Rickett – Objects in the Field

© Sophy Rickett

Sophy Rickett’s work “Objects in the Field’ (Rickett, 2012) was made at the University of Cambridge dining an artistic fellowship with the Institute of Astronomy. She met with a retired astronomer, Dr Roderick Willstrop, used images of his which he said were no longer of scientific interest, reprinted them by hand and altered them to look as she felt best suited the images. The images are shown, some on black and white, some with added intense colour, along with a story about her engagement with Dr Willstrop and important (to her) events of remembered visual clarity including her need for glasses and how when she first had them ‘for the first time I can see clearly beyond the middle distance. The tree I am looking at is alive, each and every leaf a separate, distinct entity’.

In an interview with Sharon Boothroyd, (Boothroyd, 2013) Rickett says ‘the project tells the story of my encounter with Dr Willstrop …… it looks at my way of aligning our very different practices ….. but in the most part I fail. So the work comes to be about a kind of symbiosis on the one hand, but on the other there is a real tension, a sense of us resisting one another …… I still don’t feel completely free to do just anything I want with his negatives – even once I had begun with the printing and writing the story I would check with him that he was happy with what I was doing’. Rickett is aware that she understood only a small fraction of Willstrop’s work and alludes to that in the story that sits alongside the exhibition ‘I see just the the beginning of what is to pass between them, a fragment of story as it begins to unfold’. Jeffreys comments that ‘the work stages an opposition between the ‘artistic’ and the scientific handling of an image, thereby presenting a more open form of engagement with the inter-relationship between the two’ (Jeffreys, 2014). Are the two views opposed or just the opposite sides of the same coin? Is opposition necessarily confrontational or can it be used to expand understanding?

Postmodernism:

Postmodernism as a term has been used from the 1970’s. There is not a single style on which it is based, and it came about as a reaction to modernism. Modernism was generally based on a positive view on life and a belief in progress while postmodernism has come from a more sceptical viewpoint, often involving looking at layers of meaning and multiple interpretations of any work. Postmodernist work can be funny, argumentative and is often controversial. Anything goes – provided that is, that you can argue the reason for what you are doing. Willete argues ‘Postmodernism is characterised by self-conscious and deliberate intertextuality……. Because society manipulates the social being who is proved to be infinitely malleable, Postmodernism no longer believes in the Modernist possibility of evolution towards a goal. There is only arbitrary change, determined by the dominant class for its own purposes.’ (Willette, 2012). While Wells defines it as ‘the postmodern represents a critique of the limitations of modernism with its emphasis on progress and…… on the materiality of the medium……… the collapse of certainty, a loss of faith in explanatory systems’ (Wells, 2009).

Both of these works rely on the combination of images and words to tell a story. However, the meaning of the story is not fixed, it also depends on your personal interpretation, which will partly depend on where and when you see them and how you are feeling at the time. It will also depend on your previous experience of similar works and how you reacted to them.

I find Rickett’s work is the most accessible of the two pieces, that is possibly because I am initially a scientist by training and have moved across into an ‘arts’ field. I can see it from both sides of the playing field. The images were taken more than 30 years ago, of events that took place thousands of years in the past, deep time, and which will never be replicated. Time has gone by. Present interpretation can either be scientific – that was what happened then – or artistic – that can make a story now. Both are correct, relevant and valid. The tale expands the piece, allows you to, possibly, understand more of Rickett’s thought processes.

In the work by Calle the words written by ‘X’ form an integral part of the story, they are the starting point. The genesis. Without seeing the whole exhibition live it is impossible to read all the individual responses by the 107 women. There is a book, but that doesn’t include the video responses, or possibly all the images. The original project is also in French as is the email. Looking at the images online gives you a partial viewpoint, not the immersive experience of seeing it ‘live’. So my, and countless others, interpretations form yet another layer, I am looking at other people’s responses and formulating my own. Responding to the concept rather than the actuality. A very postmodern approach.

References

Boothroyd, S. (2013). Sophy Rickett. [online] photoparley. Available at: https://photoparley.wordpress.com/2013/12/03/sophy-rickett/ [Accessed 25 May 2018].

Chrisafis, A. (2007). Interview: Sophie Calle. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jun/16/artnews.art [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Chrisafis, A. (2007). Interview: Sophie Calle. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jun/16/artnews.art [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Fisher, C. (2009). Sophie Calle: Take Care of Yourself. [online] The Brooklyn Rail. Available at: https://brooklynrail.org/2009/06/artseen/take-care-of-yourself [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Harris, C. (2010). Sophie Calle, Take Care of Yourself – a-n The Artists Information Company. [online] a-n The Artists Information Company. Available at: https://www.a-n.co.uk/reviews/sophie-calle-take-care-of-yourself/ [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Jeffreys, T. (2014). Objects in the Field – The Learned Pig. [online] The Learned Pig. Available at: http://www.thelearnedpig.org/objects-in-the-field/900 [Accessed 25 May 2018].

nhs.uk. (2016). Borderline personality disorder. [online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/borderline-personality-disorder/ [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Rickett, S. (2018). Works. [online] Sophy Rickett. Available at: https://sophyrickett.com/work#/objects-in-the-field-1/ [Accessed 25 May 2018].

Slow Words. (2016). Take care of yourself – Slow Words. [online] Available at: http://www.slow-words.com/take-care-of-yourself/ [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Wells, L. (2009). Photography. 4th ed. London: Routledge, p.349.

Willette, J. (2012). Postmodernism in Photography | Art History Unstuffed. [online] Arthistoryunstuffed.com. Available at: https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/postmodernism-in-photography/ [Accessed 25 May 2018].